CountBio

Mathematical tools for natural sciences

Statistics for Machine Learning

Nonlinear Regression

The method of nonlinear regression models the nonlinear relationship between the independent(predictor) variable X and the dependent(response)

variable Y.

We should first understand the two terms "linear relationship" and nonlinear relationship" between the predictor and response variables.

Suppose, a data consists of a response variable Y having a linear relationship with predictor variables $X_1$, $X_2$, $X_3$ and $X_4$. Using the method of multiple linear regression, we fit a linear relationship of the form,

Examples for linear regression models(functions)

$~~~~~y~=~\beta_0~+~\beta_1 x ~~~~~~~~~~$ (simple linear relation ) $~~~~~y~=~\beta_0~+~\beta_1 x^2~+~\beta_2 x^2~+~\beta_3 x^3~~~~$ (cubic polynomial curve)Examples for nonlinear regression models(functions)

$~~N(t) = \beta_1 \large{e}^{\small -\beta_2 t} ~~~~~~$ (Exponential decay curve in radioactivity) $~~V(x)~=~\dfrac{\beta_1 x}{\beta_2 + x}~~~~~~~~$ (Michaelis Menton equation in enzyme kinetics) $~~P(t)~=~\dfrac{\beta_1}{1~+~\beta_2 {\large e}^{-\beta_3 t}}~~~ $ (Logistic equation in population models) From the above sets of equations, we note the following:$~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$

Nonlinear Least Square Regression method

Once the data set (X,Y) is given, we can fit a nonlinear model through the data points by the method of Leasr Square Regression, on the similar line as the linear regression. However, the minimization procedure with a nonlinear function is much more complicated than that we encountered in linear regression. It involves numerical methods. In the sections below, a shorter form of the methodologies with essential steps is presented, skipping the details of the downstream algorithms. Many sophisticated algorithms have been developed for performing the nonlinear least square minimization. We will also learn a block level understanding of some of the important algorithms, without going into detailed steps. Let the problem in hand has p coefficients $\beta_1$, $\beta_2$,$\beta_3$,.....,$\beta_p$ and m predictor variables denoted by $X_1$,$X_2$,$X_3$,....,$X_m$. Let Y be the response variable. The nonlinear regression model is assumed to be of the form, Hypothesis testing regression coefficients

In linear regression theory, the standard error $SE(b_j)$ of an estimated parameter $b_j$ is an unbiased estimator of the corresponding

population variance $\sigma_j$. Using this fact, a statistical t-test was constructed to test the hypothesis on the parameter $\beta_j$.

These type of exact hypothesis test is mathematically possible in nonlinear regression theory. Hypothesis testing can be done only using

approximate inference procedures.

For a nonlinear regression model, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) is computed using the Sum of Squared Error (SSE) from the data points $(x_i, y_i)$

and the regression function $f(b_1,b_2,...,b_p; .x_1,x_2,...,x_m)$ as,

\begin{equation}

Mean~Squared~Error~(MSE) ~~~~~S^2~=~{\displaystyle\dfrac{SSE}{n-p}} ~=~ \dfrac{\displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - f(\overline{b}, \overline{x}))^2}{n-p}

\end{equation}

The above MSE is not an unbiased estimator of the corresponding population varience $\sigma^2$. But the bias is small when the sample size is large.

The mathematical theory says that when the error terms $e_i$ are normally distributed and the sample size is large, the sampling distribution of the coefficients $\overline{b}$ is approximately normal.

In this case, an approximate varience of the regression coefficients are derived as,

Statistical test

For a given parameter $b_j$ of the model, we can get the estimated standard deviation $s(b_j)$ using the variance matrix given by the equation(5) above. Based on this, an approximate $(1-\alpha)100\%$ confidence interval for $\beta_j$ can be defined as,Validity of the large sample assumption

Ideally, if the sample size is large enough, the large sample assumtion made in the estimation of approximate quantities is valid. How do we know that the given sample size in our data is large enough so that we are safe to use large sample assumption? One indication is the quick convergence of the procedure during the iterative estimation of coefficients. The quick convergence indicates that the linear approximation to nonlinear model is a good approximation and hence the asymptotic properties of regression estimates are good enough. Many other procedures mentioned in the literature to check the validity of this assumption. See the following reference (an e-book): http://www.cnachtsheim-text.csom.umn.edu/kut86916_ch13.pdf Some Popular nonlinear models in Life Sciences

Quardratic Polynomial

$~~~~~~Y~=~b_0+b_1X+b_2X^2~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Example: Hardy-Weinburg equationExponential function

$~~~~~~Y~=~a e^{bX}~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Example: Exponential population growth $~~~~~~Y~=~a e^{-bX}~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Example: Radioactive decay, light absorptionPower law

$Y~=~a X^{b}~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Example: Metabolic scaling theory, biomass production, cell divisionLogarithmic

$Y~=~a~+~b~log(X)~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Example: logarithmic phase of bacterial growthRectangular Hyperbola

$Y~=~\dfrac{ax}{b+x}~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Example: Michaelis-Menten equation in enzyme kineticsLogistic Function

$Y~=~\dfrac{L}{1 + e^{-k(x-x_0)}}~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Example: Population growth, tumor growth, autocatalytic $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ reactions in enzyme kineticsLog-Logistic Function

$y~=~\dfrac{d}{1~+~\large{e}^{b[log(X) - log(c)]}}~~~~~~~~$Example: Dose and time response curves of drugsGaussian function

$y~=~a \large{e}^{-b~x^2}~~~~~~~$ Example: Probability density distributio of continuous variables The general shape of these functions are plotted in Figure-1 below: Nonlinear Regression in R

R has many library functions to perform nonlinear regression. The following three functions from stats library are prominently

used:

1. $~~~~$ Example-1 : Exponential fit with lm() function

The exponential function can be converted to a linear function through log transformation.

We obtain the coefficients of exponential function from the coefficients of this linear fit.

Let the exponential function to be fitted be of the form,

$~~~~~~~~~~~~~~y~=~b_1~{\large e}^{b_2 x}$

Taking natural logarithm of both the sides, we get

$~~~~~~~~~~~~~~log(y)~=~log(b_1)~+~b_2 x$

Denoting $ y_l~=~log(y), ~~~c = log(b_1)$, we write above expression as,

$~~~~~~y_l~=~c~+~b_2 x~~~~~~~~~~~~$(Equation of a stringht line)

We now fit $y_l~=~log(y)$ versus x using the $lm()$ funciton in R to get the slope $b_2$ and the intercept c.

From this, we can recover the original coefficients of exponential fit as,

$~~~~~~~~~~b_1={\large e}^c~~~~and~~~~~b_2 = b_2$.

The For many additional parameters and their usage, typeIn R, the function lm() performs the linear regression of data between two vectors. It has the option for weighted and non-weighted fits, as well as nonlinear curve fitting. The function call with essential parameters is of the form,lm(formula, data, subset, weights) where, $formula ------> is the formula used for the fit. For linear function, use "y~x" $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ The intercept term is included by default in the formula format. $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ Use"y ~ x-1" or"y ~ 0 + x" to remove the intercept.data --------> data frame with x and columns for datasubset ------> an optional vector specifying subset of data to be used.weights ------> an optionl vector with weights of fits to be used. Weights are inversly proportional to the variences.

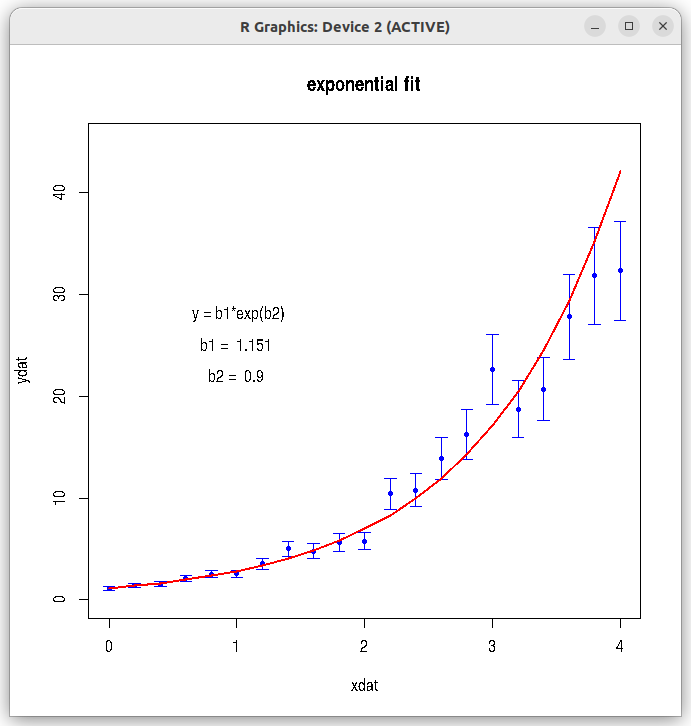

## fitting an exponential function to data ## fit of the form y = b1*exp(b2 * x) ## taking log on both sides, log(y) = log(b1) + b2*x ## so, we fit log(y)~x ## log(b1) is intercept. So, b1 = exp(intercept) ## b2 is the slope, as we get. ## then, y_fitted = b1*exp(b2*x) ## -------------------------------------------------- ## read data file dat = read.csv(file="./data_files/exponential_data.csv", header=TRUE) xdat = dat$xdat ydat = dat$ydat err = dat$error ## error propagation while taking log of variable ydat. err_log = err*(log(ydat)/ydat) ## Call the lm() function for linear fit between log(ydat) and xdat. res = lm(log(ydat)~xdat, data = dat, weight = 1/err_log) ## print the summary of results print(summary(res)) ## retreive the slope and intercept intercept = res$coefficients[[1]] slope = res$coefficients[[2]] ## Get back the coefficient b1 of exponential fit. b1 = exp(intercept) b2 = slope # Fitted y values y_fitted = b1*exp(b2*xdat) ## Plot the data points with errors and fitted curve. plot(xdat, ydat, col="blue", pch=20, main="exponential fit", ylim=c(0,45)) arrows(xdat, ydat+err, xdat, ydat-err, angle=90, code=3, length=0.06, col="blue") lines(xdat, y_fitted, type="l", lw=2, col="red") b1_string = paste("b1 = ", round(b1, digits=3) ) b2_string = paste("b2 = ", round(b2, digits=3) ) text(1,28, " y = b1*exp(b2)") text(1,25,b1_string ) text(1,22, b2_string)

Running the above script in R prints the following output lines and graph on the screen:

In the above output, we gather that 1. The slope = 0.899 and the intercept $c=0.14106$. From this, $b_1 = e^c = e^{0.14106}~=~1.1515$ and $b_2 = 0.899$. Therefore, the fitted curve is $y = b_1 e^{b_2}~=~1.1515 \large{e}^{0.899}$ 2. The adjusted $r^2$ value is 0.991, indicating a very good exponential fit to the data. 3. The significance tests (t-tests) for intercept and slope have yielded very small p-values, indicating a good statistical significance. The plot created by the script with original data points and the fitted curve is shown below:Call: lm(formula = log(ydat) ~ xdat, data = dat, weights = 1/err_log) Weighted Residuals: Min 1Q Median 3Q Max -0.36534 -0.13895 -0.03797 0.19807 0.42882 Coefficients: Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) (Intercept) 0.14106 0.02614 5.396 3.31e-05 *** xdat 0.89983 0.01912 47.061 < 2e-16 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 Residual standard error: 0.2565 on 19 degrees of freedom Multiple R-squared: 0.9915, Adjusted R-squared: 0.991 F-statistic: 2215 on 1 and 19 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Example-2 : Polynomial fit with lm() function

In polynomial fit, the data is fitted with a polynomial function of degree n of the form,

$~~~~~~~~~~y(x)~=~b_0 + b_1 x + b_2 x^2 + b_3 x^3 + ........+ b_n x^n$

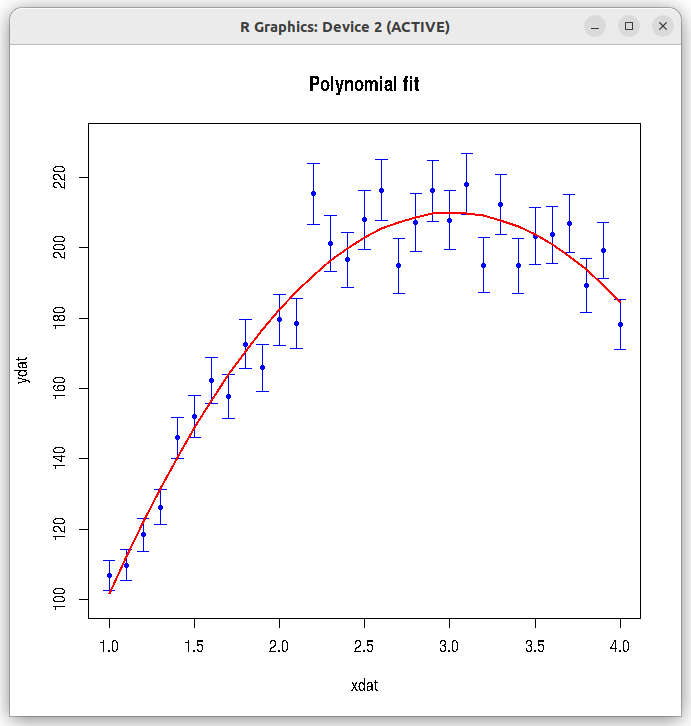

In this example, we fit a (quardratic) polynomial of degree 2 using the ## fittng a data to polynomial dat = read.csv(file="./data_files/polynomial_data.csv", header=TRUE) xdat = dat$xdat ydat = dat$ydat error = dat$err ## If you remove raw=2, returns coefficients of orthogonal polynomial fit (dont use it). ## Use with raw=2, so that normal fitting values of coefficients are returned. mod <- lm(ydat ~ poly(xdat, 2, raw=2), data = dat, weights=1/error) ## Returns normal poplynomial fit coefficients b0, b1, b2 and b3. ## mod <- lm(formula = ydat ~ xdat + I(xdat^2) + I(xdat^3), weights=1/error) ## Fitted without first order xdat term. ## Computes coefficients b0, b2 and b3, omitting b1. ## Looks better than second degree polynomial with xdat term shown above. ## mod <- lm(formula = ydat ~ I(xdat^2) + I(xdat^3), weights=1/error) print(summary(mod)) y_fitted = mod$fitted.values plot(xdat, ydat, col="blue", pch=20, main="Polynomial fit", ylim=c(100,230) ) arrows(xdat, ydat+error, xdat, ydat-error, angle=90, code=3, length=0.06, col="blue") lines(xdat, y_fitted, type="l", lw=2, col="red")

Running the above script in R prints the following output lines and graph on the screen:

We can see that the adjusted R-square for the fit is 0.9506, indicating that it is a good fit to the data. Similarly, the results of t-test and F-test for the fit are also giving extremly low p-values. The best fit curve is of the form, $~~~~~~~y(x)~=~-32.811~+~160.231~x~-~26.549~x^2$ The plot created by the script with original data points and the fitted curve is shown below:Call: lm(formula = ydat ~ poly(xdat, 2, raw = 2), data = dat, weights = 1/error) Weighted Residuals: Min 1Q Median 3Q Max -5.0216 -2.0250 -0.1788 2.2386 7.8692 Coefficients: Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) (Intercept) -31.811 10.681 -2.978 0.00593 ** poly(xdat, 2, raw = 2)1 160.231 9.695 16.527 5.64e-16 *** poly(xdat, 2, raw = 2)2 -26.549 1.960 -13.544 8.15e-14 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 Residual standard error: 3.031 on 28 degrees of freedom Multiple R-squared: 0.9539, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9506 F-statistic: 289.7 on 2 and 28 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

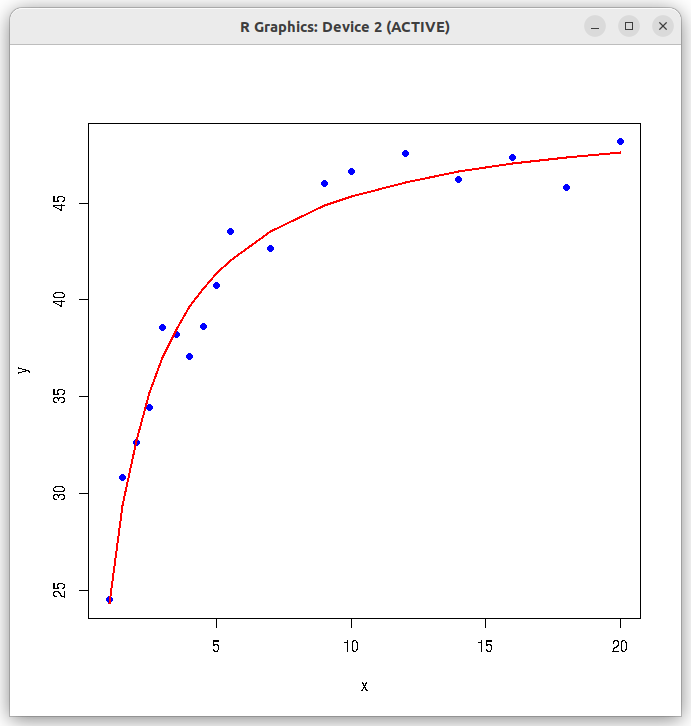

Example-3 : Nonlinear fit with nls() function

We will fit the Michaelis-Menton data of enzyme kinetics using nls() function of R stats library.

The function is of the form,

$~~~~~~~~~~~~~~y(x)~=~\dfrac{b_1 x}{b_2 + x} $

The R script presented below reads the data file "MM_kinetics_data.csv" and performs a nonlinear fit of MM kinetics form to the data.The function call with some of the essential parameters is of the form, nls(formula, data, start, algorithm, weights, ....) where,formula ----------> is the relation between y and x that we want to fit.data ------------> is the data frame with x,y and error(if used) for each data point.algorithm ---------> name of algorithm in string form. Three choices are there. Gauss-Newton algorithm by default, "plinear" for Golub-Pereyra algorithm for partially linear least-squares models and "port"’ for the ‘nl2sol’ algorithm from the Port libweights ------------> vector of weights, which is inverse of varience for each data point.start -------------> a vector of initial values for the parameters. (see manual for other parameters)

## Fitting MM kinetics (nonlinear) curve using nls function. # Read the data file into data frame dat = read.csv(file="./data_files/MM_kinetics_data.csv", header=TRUE) ## Extract x and y data vectors y = dat$y x = dat$x ## Call the nls function with MM kinetics formula res <- nls(y ~ (b1 * x) / (b2 + x), start=list(b1=35, b2=2.0)) ## Print the summary of results print(summary(res)) ## Plot datav points and the fitted curve. plot(x,y,col="blue", pch=20, cex=1.3) lines(x, predict(res), type="l", lwd=2, col="red")

Running the above script in R prints the following output lines and graph on the screen:

Formula: y ~ (b1 * x)/(b2 + x) Parameters: Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) b1 50.15639 0.66250 75.71 < 2e-16 *** b2 1.06121 0.07473 14.20 1.73e-10 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 Residual standard error: 1.294 on 16 degrees of freedom Number of iterations to convergence: 6 Achieved convergence tolerance: 1.971e-06